In a disaster, the psychological “footprint” greatly exceeds the size of the medical “footprint” (J.M. Shultz, 2010). While much of the United States is focused on “reopening” and going back to in-person work, school, and social activities, with images in the news of joyous reunions of families and friends, there is the shadow of yet another COVID-19 wave entering our awareness: the mental health impact of the pandemic and its individual, family, and community consequences. As the country and world come to terms with both the collective trauma of this pandemic and its inequitable outcomes, it is more important than ever for psychiatrists to understand the role of trauma in behavioral health disorders, and to work to mitigate its impact for our patients both in our clinics and beyond. The basic principles of trauma-informed care (TIC) should serve as a guide to rebuilding and reimagining our systems of care to meet the surging needs of Americans acutely affected by the pandemic, as well as those whose experiences of violence, abuse, neglect, bias, loss and poverty have long predisposed them to both mental health disorders and revictimization by the systems that are supposed to help. As psychiatrists, we have an understanding of trauma from a neurobiological and psychosocial perspective. This understanding can help us not only as we treat the mental health consequences on an individual level, but also in partnering with the organizations, groups, and institutions that our patients interact with outside the health care system.

SAMHSA defines traumatic experience as “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being (SAMHSA 2014).” This definition is intentionally broad; most Americans continue to be affected by some aspect of the public health, social and political upheaval of the last year that has been physically or emotionally harmful. Of course, only a small minority of individuals will develop PTSD. But as the country moves on and the economy recovers, the people left behind are likely to be those most affected by the pandemic trauma – those with adverse childhood experiences, with prior mental illness, those affected by gender-based violence, the chronically discriminated against, those already living close to the edge of the cliff of good health . In other words, our patients.

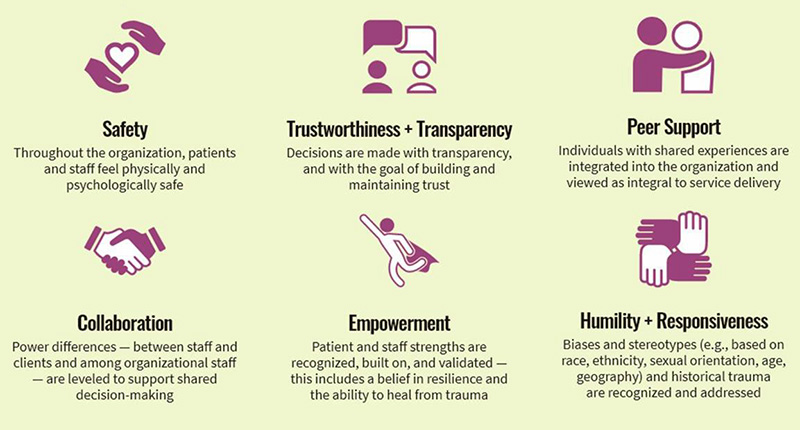

Trauma-informed care demands that we recognize the widespread impact of trauma not just on our patients but also in their families, in our staff and colleagues, and in our own lives. As psychiatrists we also must understand that the paths for recovery do not always fall neatly into medical models of treatment that are prioritized in insurance-based payer structures. Our patients’ struggles do not only present in our offices and clinics. We should seize the opportunity of this moment of rebuilding to re-think systems of care. What would care look like if it integrated the basic principles of TIC: safety, transparency and trustworthiness, collaboration, empowerment, humility and responsiveness, and peer support into all the institutions with which our patients interface? (see chart above – SAMHSA, 2014).

Psychiatry can have a positive role in advocating for trauma-informed services. Several years ago, we partnered with New York City to create a model of psychiatric care integrated into the five Family Justice Centers administered by the NYC Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender Based Violence (NYC ENDGBV) (Weiss 2017). These centers, adjacent to the District Attorney’s offices, host social services, civil legal, counseling, and advocacy-based organizations and agencies dedicated to helping survivors of domestic violence and sex trafficking. Through this work we discovered that this type of partnership between mental health and service-oriented systems outside of health care not only reduces barriers to care for individuals but enhances the potential for positive impact of both psychiatric care and advocacy. For example, trauma-impacted clients frequently seek legal assistance at times of highest stress, when they are most vulnerable and emotional. In practice areas such as family law, immigration, child welfare, criminal law and others, by necessity, clients must share some of the most intimate and painful details of their lives at a time when the stakes are highest to a system that is likely to misinterpret the manifestations of traumatic stress as defects of character or admissions of guilt. Mental health practitioners know that working with patients who are survivors of interpersonal and sexual violence demands that we manage our own emotional reactions to confronting violence and its effects while at the same time offering sensitive and responsive care. We also learn how trauma impacts the nervous system, attachment models, and perceptions of safety and threat. Understanding of the role of transference and countertransference is an essential component of our training. However, our colleagues in the legal and criminal justice systems often do not have the advantage of this baseline understanding.

Earlier this year, our team partnered with the NYS Office for Victim Services as well as the New York Legal Assistance Group to provide a training series to legal professionals entitled “Trauma-Responsive Lawyering.” The training covered the intersection of mental health and trauma, the neurobiology of trauma, revictimization, grounding tools, safety assessment, vicarious traumatization, and working with marginalized populations. Goals of the project included educating legal professionals to identify and define trauma, vicarious trauma, and trauma reactions; recognize and understand concrete strategies and practices for mitigating the impact of primary and secondary trauma; and comprehend and implement simple self-care practices and coping strategies while working with crime victims and their families. The sessions combined didactic instruction and interactive components ranging from polls, Q&A, discussion, and breakout sessions. Overall, 522 people registered for the course. It was clear based on participation levels of attendees and feedback following each session, that legal professionals are eager for continued trainings on these issues. This was one of the only trainings to our knowledge that was co-led by both mental health professionals and legal professionals. We strongly believe that this partnership was a key to the training’s success, and that continued partnerships across interdisciplinary providers on trainings is essential to better serve clients as well as to providing educational learning that is impactful and meets the goals of TIC.

This outreach beyond the usual silo of psychiatry is even more pressing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Together with the increased psychological stress experienced by all during this crisis, as well as disruptions to accessing institutions of service and health care, there is an urgent need for society and systems of care to provide trauma-responsive care to everyone. Psychiatry has the opportunity, knowledge, and skill to help shape this conversation. “There is no health without mental health.”

Elizabeth M. Fitelson, MD, is Associate Professor of Psychiatry at CUIMC, and Director of The Women’s Program at Columbia University Department of Psychiatry. Obianuju O. Berry, MD, MPH, is Medical Director at NYC Health and Hospitals Gender-Based and Domestic Violence Mental Health Collaboration, and is Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, at NYU.

References

Schultz, J.M. 2010. “Psychological footprints.” Disaster and Extreme Event Preparedness Center, University of Miami.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014 https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/social-determinants-health/projects/dr-camara-jones-explains-cliff-good-health

Weiss M, Benavides MO, Fitelson E, Monk C. The Domestic Violence Initiative: a private-public partnership providing psychiatric care in a nontraditional setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:212